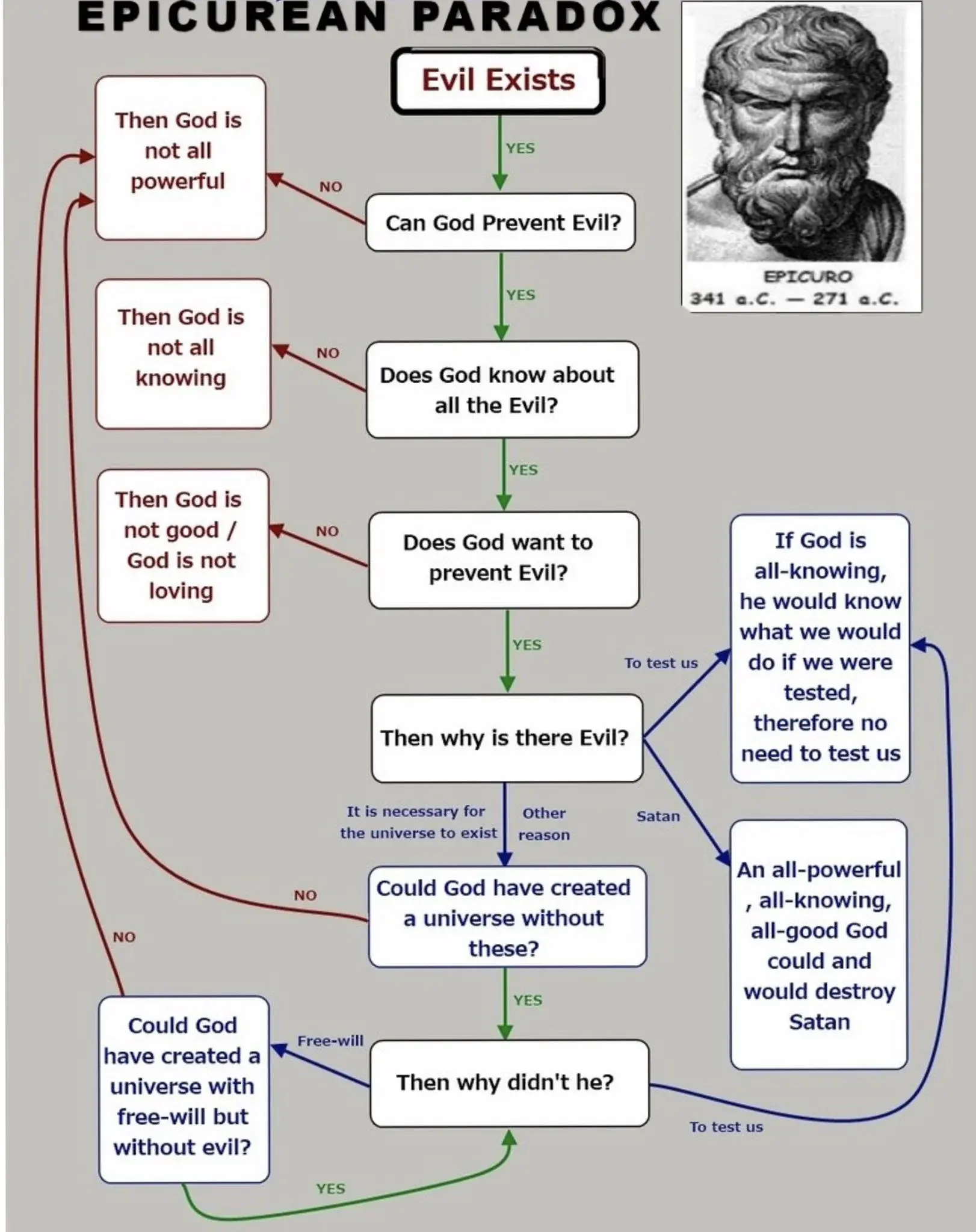

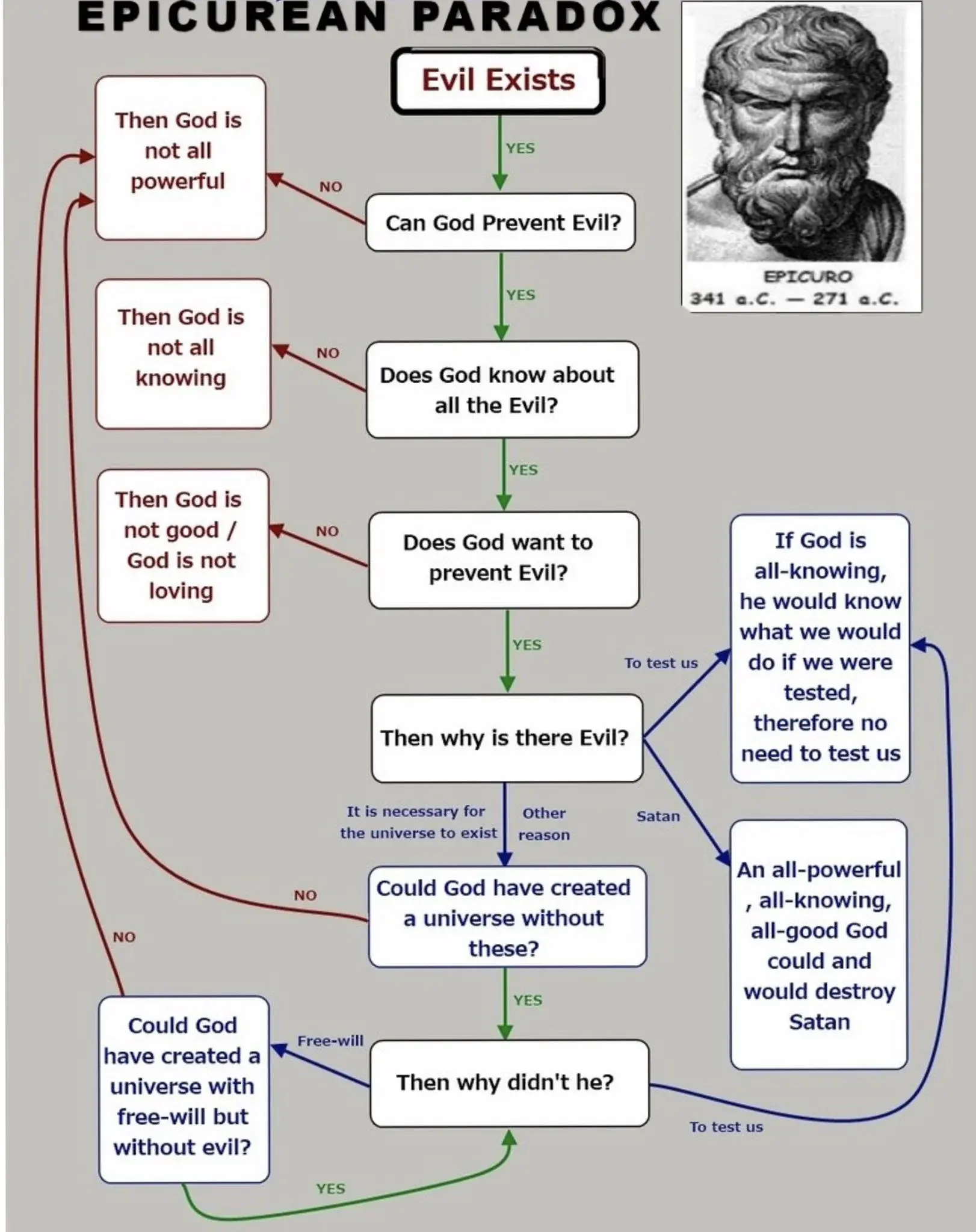

A cool guide to Epicurean Paradox

A cool guide to Epicurean Paradox

A cool guide to Epicurean Paradox

You forgot the actual Epicurean belief. God(s) exist but they don't give a fuuuuuuuuuck.

Epicurus was the first deist.

Really more an atheist.

Don't forget that not long before him Socrates was murdered by the state on the charge of impiety.

Plato in Timeaus refuses to even entertain a rejection of intelligent design "because it's impious."

By the time of Lucretius, Epicureanism is very much rejecting intelligent design but does so while acknowledging the existence of the gods, despite having effectively completely removed them from the picture.

It may have been too dangerous to outright say what was on their minds, but the Epicurean cosmology does not depend on the existence of gods at all, and you even see things like eventually Epicurus's name becoming synonymous with atheism in Judea.

He is probably best described as a closeted atheist at a time when being one openly was still too dangerous.

wouldn't that be more like an agnostic than an atheist?

since atheist believes that gods don't exist

It may have been too dangerous to outright say what was on their minds,

That alone has held back a lot of progres throughout the centuries.

"God works in mysterious ways"

The cope that always comes across when I hear this is intesne

imo every religion ever is a cope. All of those elaborate ideas about supernatural beings and alternate planes of existence to somehow cope with the fact that one day the good man, and the evil man, will both die and rot just the same.

It feels incredibly unjust for good men to die the same way evil men do, and for a lot of people that's too much to handle. We as humans have such a strong sense of "fairness" that we attempted to structure our entire society around the idea of justice for all, and so by comparison nature feels cruel and unfair, you can either learn to live with that, or tell yourself really really hard that it's not the end :) after they die the good man will be happy! and the evil man will get the punishment he deserves!

now layer that with milenia of different ideas about what qualifies you as "good" and "evil" and you've got religion.

This is my personal opinion, and honestly I don't mind nor care how the other person deals with their existential dread, as long as they aren't bigots about their way of coping.

If there is a ‘god’ then they are a fucking asshole.

"If there is a god, he must ask me forgiveness."

-Scrawled on the walls of a Nazi concentration camp cell

All religion is not about logic or reason, rather it is about identity. You can join a club for scale model trains, and you can join it for the only reason that you want to and because you enjoy it. You then identify as a member of the train club. It becomes part of your identity.

Religion is similar except it adds a dogma and doctrine that defines your entire world view. To lose this world view is to lose your identity. People would rather die than lose their identity because psychologically one’s identity is synonymous with their life.

The only way a person will lose religion is if they have decided for themself that it’s time for change. Much like an addict, it a personal identity change. You have to say to yourself, I am no longer an alcoholic or I am no longer a Mormon. There is no amount of convincing, rationality, evidence or influence that can change a person until they are ready and willing. It’s transformative and traumatic. You just have to accept those who are lost to it.

Maybe God is studying ethics, and we are his show and tell assignment.

Or we're in a microverse powering his spaceship.

To nibble further at the arguments for God: free will is absurd.

If god is all knowing and all powerful, then when he created the universe, he would know exactly what happened from the first moment until the last. Like setting up an extremely complex arrangement of dominoes.

So how could he give people free will? Maybe he created some kind of special domino that sometimes falls leftward and sometimes falls rightward, so now it has "free will". Ok, but isn't that just randomness? God's great innovation is just chance?

No, one might argue, free will isn't chance, it's more complex than that, a person makes decisions based on their moral principles, their life experience, etc. Well where did they get their principles? What circumstances created their life experience? Conditions don't appear out of nowhere. We get our DNA from somewhere. Either God controls the starting conditions and knows where they lead, or he covered his eyes and threw some dice. In either case we can say "yes, I have free will" in the sense that we do what we want, but the origins of our decisions are either predetermined or subject to chaos/chance.

A good read on the inverse of what you're stating, namely that free will is logical:

https://www.mit.edu/people/dpolicar/writing/prose/text/godTaoist.html

Got to be honest, I started reading that, saw how long it was and stopped. Would you want to share the gist?

That was an excellent read, thank you!

You see, shit like this is why I think some of the Eastern philosophers like Xunzi hit the mark on what "God" is: God is not a sentient being, God does not have a conscious mind like we do, God simply is.

Of course, those people didn't call this higher being the God, they called it "Heaven", but I think it's really referring to the natural flow of the world, something that is not controlled by us. Maybe the closest equivalent to this concept in the non-Eastern world is "Luck" -- people rarely assign "being lucky" to the actions of insert deity here, it simply happens by the flow of this world, it is not the action of an all-knowing, all-powerful deity. But like I said, it's merely the closest approximation of the Heaven concept I can think of.

The side effect coming out of this revelation is that, you can't blame the Heaven for your own misfortunes. The Heaven is not a sentient being after all!

This is always bizarre because "evil exists" is taken as a given and I don't think it does. Evil is just a judgment call made by humans about the intentional and uncoerced actions of other humans; nothing less volitional than that can be argued as evil.

You can simply replace evil with suffering, or ig a christian context might say sin? The point is the paradox is a structure, if any choice of word makes it work, then it works.

Evil is just a judgment call made by humans about the intentional and uncoerced actions of other humans

Cancer is not an intentional and uncoerced action of other humans.

Earthquakes and tsunamis are not intentional and uncoerced actions of other humans.

If an omnipotent and omnibenevolent god existed, there would be no justification for these.

This guide lacks the branch where people's sense of good and evil differs from the God's one.

So wait the argument is that yes, by human definition, God is evil, but that he thinks all the atrocities in the world are totally awesome? That doesn't make him less evil

More like, on the scale of mortal vs god, the things that are important to us either aren't important to god(s) or may be so insignificant to be actually imperceptible.

As a thought experiment, say you get an ant farm. You care for these ants, provide them food and light, and generally want to see them succeed and scurry around and do their little ant things. One of the ants gets ant-cancer and dies. You have no idea that it happened. Some of the eggs don't hatch. You notice this, but can't really do anything about it. So on, and so forth. Now - think about every single other ant you've passed by or even stepped on without even noticing during your last day outside the house. And think about what those ants might think of you, if they could.

Now an argument that a god is omniscient and all powerful would slip through the cracks of this because an omniscient god WOULD know that one of their ants had ant-cancer and an all-powerful one would be able to fix it. But the sheer difference in breadth of existence between mortal and god may mean that such small things are beneath their attention. Or maybe he really does see all things at all times simultaneously down to minute detail. We don't know. It is fundamentally unknowable to mortals. Our scales of ethics are incomparable.

We also don't know if the ethical alignment of a god leans toward balance rather than good. It would make sense, in a way, if it did. Things that seem evil to us are in fact evil, but necessary in pursuit of greater harmony. Or in fact even necessary to the very function of the universe from a metaphysical perspective. If we assume the existence of a god for this argument it leads to having to assume an awful lot more things that we can't really prove or test one way or the other. But one thing that seems pretty self evident is that the specific workings of a god are fundamentally unknowable to mortals specifically because we are not gods. We don't have a perspective in which we can observe it so any argument made in any direction about it is pretty much purely conjecture by necessity.

The problem my agnostic ass meets with good ol' Epi is the disingenuousness inherent in assuming "Godly" rationale to "human logic" semantics. My dude, people can't agree on human meaning and I'm supposed to make assumptions on God?

Why test if It knows the result of the test?

Geez Epic Manster, I know they didn't have spring mattresses in your day but the mattress factory also knows the result my mattress should have gotten at testing but tested it anyways...because the testing provides the necessary shape.

I still maintain my agnosticism and keep my two extremes whenever I don't feel like just being sure it's all bullshit anyways:

If God exists, it doesn't care for our suffering for reasons wholly beyond us (like a greater suffering of its own and why not, it's shit all the way down).

God exists, cares, is a bit sad, but we're all fucking mattresses where the cosmos is gonna poke, prod, and simulate fucking atop of us until we reach the appropriate factory required settings.

I already had coffee tho, so the middle atheist ground is in effect; none of it real, nothing matters except trying to not be total cockwaffles so everyone else can enjoy their nihilism too.

The problem my agnostic ass meets with good ol’ Epi is the disingenuousness inherent in assuming “Godly” rationale to “human logic” semantics. My dude, people can’t agree on human meaning and I’m supposed to make assumptions on God?

I think the idea here is that this deity being perfect would give some sort of absolute underpinning to the universe, having been designed by an intelligent mind. If it's made in this systemic way, even if we don't currently comprehend it properly, given enough time, we should be able to figure out at least some of the rules, providing insight into the nature of things and the mind of the universe's creator.

I know they didn’t have spring mattresses in your day but the mattress factory also knows the result my mattress should have gotten at testing but tested it anyways…because the testing provides the necessary shape.

The mattress factory isn't claiming their process is infallible, though, and they have QC exactly because they admit this and don't want a factory defect to get out to customers. That's a big difference from the omnipotent, omniscient deity being spoken of in the paradox here.

God having different morals makes a lot of sense. If you're a super being that knows most people are going to end up eternally in a pleasurable afterlife at the end of the day, what's a little temporary suffering while we meet?

Just saying, going to work isn't so bad when I know I get to go home, maybe a grab a pizza with the money I earned on the way back.

I already had coffee tho, so the middle atheist ground is in effect; none of it [is] real, nothing matters except trying to not be total cockwaffles so everyone else can enjoy their nihilism too.

This might just be the most British summation of my own beliefs I've ever read.

The bad execution of the flow chart was bothering me enough to create a cleaner version.

The solution I have heard before that I thought was the most interesting would add another arrow to the "Then why didn't he?" box at the bottom:

Because he wants his creation to be more like him.

He's just a lonely guy. He made the angels but they're so boring and predictable. They all kowtow to him and have no capacity for evil (except for that one time). Humans have the capacity for both good and evil, they don't constantly feel his presence, and they're so much more interesting! They make choices that are neither directly in support of or opposition to himself. Most of the time, their decisions have nothing to do with him at all!

Humans have the capacity to be more like God than any of his other creations.

That would fall under the "then God is not good/not all loving". You described it as if it were a privilege, but the capacity of evil causes indescribable suffering to us and to innocent beings such as small children and animals. If God lets all of this happen just because he wants some replicas of himself or because he thinks it is such a gift to be like him despite it, he's an egotistical god.

Also, if he gets bored of pure goodness, blissfulness, and perfection, then it was never pure goodness, blissfulness, and perfection for him. Those things, by definition, provide eternal satisfaction. So he either never created that (evil branch again) or he cannot achieve those states even if we wanted to. If he cannot achieve those states even if he wanted to, if he lacks enjoyment and entertainment and has to spice his creation from time to time, then he's not all powerful.

Also, many people argue the necessity of evil as a requisite for freedom. If God needs to allow evil so we can be free, then he's bound to that rule (and/or others): not all powerful.

[slow, earnest clap]

If humans aren't predictable to this god, then that god isn't all-knowing.

Would they have been predictable had they never been created? Is conceptualizing an entire universe the same as actually creating the entire universe so it can play out?

Is there actually "free will" without evil?

why not? you can choose to eat a banana or an apple, both perfectly non evil

I will die on a hill that says a banana is more good than an apple.

Making the apple relatively more evil on the scale from good to evil.

Others may prefer an apple. But I guess that is their free will to choose so 😉

The free will is more about choosing to follow god or not. So if everything god does is good and everything they want you to do is good, you have no choice but to do those things. So you live in a perfect world but are a puppet.

An all-powerful god wouldn't be affected by such logic. They could have changed the rules to allow for free will without evil.

Didn't Epicurus live before Christianity was a thing?

In my quick searching, I can't find much info on it. It seems that he made it in response to the idea that there were Greek gods that were concerned with humanity's wellbeing and actively took a positive part in our existence. His ideas don't apply to one religion or even try to say that there is no god, rather he is just saying that the gods are too busy / unconcerned with humanity's wellbeing which was not the common view of the period.

Sounds more like he's deist or agnostic rather than what the guide implies.

I don't think it's that God couldn't create a universe without evil, it's just there's a process for making us good AND retaining our freewill.

So he's letting us help to create a universe without evil...

Evil is necessary in this process, but evil is really just God "occluded" - Satan is in this sense working for and with God in this process of teaching humans about good, hence the line "God works in mysterious ways"... We don't know the process, which is why it's faith-based.

It's like yes, your parents could give you a lifetime of pocket money all at once, but they're not going to because you have to learn patience, self-discipline, and saving up for the things you want (or can afford). You have to make choices in that process to learn about those things.

Humans are temporal... God is not.

So for God, God created a world without evil in which humans have freewill... It's already been done, instantly for God.

But we don't live on the same temporal plain.

Claiming God can't do it, is like being the kid asking for ALL the pocket money at once. Parents could do that, but they're letting time and your own temptation teach you the lessons.

That's part of the mysterious ways. But in faith, outside of time, and with the right beliefs and choices, a world without evil where people in your life still have freewill already exists... It's up to you to live there in it, in time.

...and you may end up living there anyways.

assuming you're right, he either can't or doesn't want to create that world without human suffering. Remains either evil or not all powerful.

You're assuming that the creation of suffering is evil when God does it - however it could be that if heaven exists as a place in the future where everyone's all good with what happened...

...then it might not be evil when God does it, it might only be evil when humans do it (because we're not capable of doing it in a way that's consciously creating heaven (where everyones okay with what happened) as a result... We can't arrange souls like God can. We can't live or operate outside of, or beyond time like God can.

...also, not that anyone asked, but personally - I'm an atheist. I'm just seeing how far these arguments can go with provisos like heaven, God as a time lord, and souls/at-birth soul agreements.

Oh, also God can patch up or fix up, or factor in suffering humans create, because being able to predict that something is going to happen isn't the same as causing it. Eg. I know the sun is going to rise each day up until an expected sun-death... Even if humanity creates the ability to make the sun rise, it doesn't mean the sun is currently controlled by us. Yet it's still predictable.

Does "all powerful" really mean all? I mean, a lìfe sentence is only about 30 years. Since it's all just social constructs (and even if it isn't) the precise meaning of the word could different that you'd think.

Maybe god was all powerful until they created free will and found that they made free will stronger than themselves. But since god made free will, god is still all powerful.

Like humans making machine learning. We can only influence it, not control it. Does that mean we are not in control? No, we could simply pull the plug.

God could also simply pull the plug, but likely doesn't want to because we are their creation. It's only a last resort.

Anyways, that's my two cents.

I agree that "all powerful" is an ambiguity here. For example, the famous "can he make a boulder so heavy he can't move it?"

There will always be paradoxes in the universe. So you'd have to go to each respective believer to figure out what "all powerful" means. Maybe making a utopia is impossible.

Philosophy is fun

Indeed. Omnipotence doesn't mean to be able to do impossible things, thus God can be at the same time omnipotent and loving and create a universe in which evil exists, as it is a condition to freedom.

Philosophy is indeed fun, because philosophers know it's only theory. Religion is a lot more advanced than just theory. Religion is basically the first instance of quantum computing.

Every religion has it's own truth, but every religion is the only truth. Thus truth can clearly have different states.

Religion is all states at once, but depending on it's observer, it is only one truth at any given time and place. When two states interfere with each other, (when they get onbserved at the same time and place), you can get disastrous consequences, e.i. war.

The problem with the argument is that evil is relative, and the relative knowledge of what is or isn't is something subjectively decided, not something inherently known.

We don't know if evil is relative, but you can follow the dilemma with different wording.

We don't like our wellbeing and our ability to make our own decisions taken away from us. We suffer, which is something we want to avoid in general terms. It goes beyond humanity, as many animals also seem to seek the satisfaction of their will (being it playing, feeding, instinctively reproducing, etc.) and seem adverse to harm and to losing their life.

So... If we are such creatures, it's natural we don't like situations and beings that go against this. We don't like volcanic eruptions when they're happening with us close the crater. We don't like lions or bears attacking us. We especially don't like other humans harming us as we suspect they could have done otherwise in many cases. We simply don't like these things because of our 'programming' or 'design'.

Problem? There are a few. The first is God asks us to like him when he's admitting that he is actively doing the things we dislike almost universally as human beings. That makes us fall into internal conflict and also into conceptual dilemmas. Perhaps due to our limitations, but nonetheless real and unsolvable to us.

Then you can argue that the way we are is designed by him, so why design something that is going to live, feel, think certain things as undesirable and then impose such things unto them? Let's say I cannot say that's evil, I at least can say it's impractical as it will certainly cause trouble to his mission of accepting him (and following him). If that obstacle for us is part of the plan, that's not for me to say, yet it is an obstacle in our view and experience. In human terms, all this might be classified as unfair or sadistic, which is the reasoning in the guide and how you can follow it in this perhaps closer way.

Now, about this last part, while we can argue that those terms arise from our own dispositions and might be different to other dispositions (aliens that do not experience pain, for example), is that enough to invalidate our perspective? Then what's the place of empathy, which I am assuming is also a part of God's gifts to us? What's the place of compassion, as written in many religious texts of supposedly divine inspiration? If we need to carry our dispreference, displeasure, dislikeness—suffering—and not to classify it as necessarily evil when the gods impose it to us (as it is our judgment only), then why classify it as evil in other circumstances?

I hope I am getting my new point though. What this all seems to conclude is that if the lack of respect for the suffering of the animal kingdom is not worthy of being classified as bad (for whatever reason, here I argued that because this comes to be only by our characteristics/disposition); if, therefore, we cannot say a god is evil for going against our wellbeing and against our ability to make our own decisions, then I fail to understand many other things that tend to follow religious thinking and even moral thinking.

You're getting too caught up in one particular concept of 'God' (why is it a 'he' even?).

Epicurus wasn't Christian. Jesus doesn't even come along until centuries later.

There are theological configurations in antiquity very different from the OT/NT depictions of divinity which still have a 'good' deity, but where it is much harder to dispute using the paradox.

For example, there was a Christian apocryphal sect that claimed there was an original humanity evolved (Epicurus's less talked about contribution to thinking in antiquity) from chaos which preceded and brought about God before dying, and that we're the recreations of that original humanity in the archetypes of the originals, but with the additional unconditional capacity to continue on after death (their concept of this God is effectively all powerful relative to what it creates but not what came before it).

If we consider a God who is bringing back an extinct species by recreating their environment and giving them the ability to self-define and self-determine, would it be more ethical to whitewash history such that the poor and downtrodden are unrepresented in the sample or to accurately recreate the chaotic and sometimes awful conditions of reality such that even the unfortunate have access to an afterlife and it is not simply granted to the privileged?

The Epicurian paradox is effective for the OT/NT concepts of God with absolute mortality and a narcissistic streak, and for Greek deities viewed as a collective, and a number of other notions of the divine.

But it's not quite as broadly applicable as it is often characterized, especially when dealing with traditions structured around relative mortalities and unconditionally accepted self-determination as the point of existence.

Okay, I can partially respond to this. (I'm a satanist, so don't @ me over this.)

First, we're using mortal definitions of good and evil, which may not conform to what a god would define as good and evil. Moreover, if you say that god's will is good, and that everything that happens is the will of god because that god is all-powerful, then everything is good because that is what god wills. That means that, yes, the rape of children is good, because that was god's will. If god created everything and is all-powerful, then this is a logical conclusion.

Second, you can say that god knows the outcome, but that we don't. We believe that we have choice, but god already knows what we're going to choose, even though we don't know until we make the choice. This is determinism. Under this model, god is giving us enough rope to hang ourselves, and we condemn ourselves to hell, rather than god condemning us.

That means that, yes, the rape of children is good, because that was god's will.

This is not a god worth worshipping, then.

Sure, but if there's a god, and if that god is the only one, then it doesn't matter whether you choose to worship them or not, because they have absolute power over you.

This is fundamentally the problem that Christians create with their concept of morality, i.e., all morality springs from god, and if it's god's will, then it must be good by definition.

There can't be free-will if there wasn't any choice. If there there are choices, there is the potential for evil choices.

So it's kinda like saying "if God is all powerful could He create a mountain on Earth but also make it so the Earth is a perfect sphere?" It's just pointing out that a planet that's a perfect sphere wouldn't have mountains and a planet with mountains are not perfect spheres. Which isn't exactly deep philosophical thought that needs a flow chart.

Also if proving something about religion is paradoxical proves that religion is wrong, by the same logic proving something about math or science is paradoxical proves those are wrong. Halting Problem? Math is false! Schrodinger's Cat? Physics is false!

But outside atheist dogma, most people accept there are things about the universe that are paradoxical. The Halting Problem doesn't mean we should discard mathematics, Schrodinger's Cat doesn't mean we discard Physics. Following this trend means that all of the efforts by atheists to point out paradoxes in religion doesn't accomplish anything.

There can’t be free-will if there wasn’t any choice. If there there are choices, there is the potential for evil choices.

I am hungry. I decide to make myself a sandwich, with peanut butter, and one of the following:

None of these are evil, yet they are choices.

Also if proving something about religion is paradoxical proves that religion is wrong, by the same logic proving something about math or science is paradoxical proves those are wrong.

This is a false equivocation. Proving that a fundamental part of a religion (such as a tri-omni god) to be paradoxical means everything built off of that idea is wrong. The same applies for math and science, but when large swaths of things in math and science get proven wrong because of a underling assumption that later turned out to be false, we get closer to the truth. That's how we went from a geocentric model, to a heliocentric model, to the understanding that there isn't any discernible center to the universe.

Halting Problem? Math is false! Schrodinger’s Cat? Physics is false!

Those problems do not prove math and science to be false, as they do not challenge fundamental assumptions.

Following this trend means that all of the efforts by atheists to point out paradoxes in religion doesn’t accomplish anything.

Nah. This paradox quite clearly debunks the idea of a tri-omni god presiding over the universe. This is a fundamental assumption within some major religions, and it's wrong. By extension the ideas built off of it are wrong.

Do the same for math and science and you'll lead to new discoveries.

I am hungry. I decide to make myself a sandwich, with peanut butter, and one of the following:

undefined

strawberry jam

honey

grape jelly

None of these are evil, yet they are choices.

If I throw a jar of strawberry jam at your head, is that not an evil choice? You chose to make a sandwich with that jam, but someone else can choose to do something evil in the same situation.

Those problems do not prove math and science to be false, as they do not challenge fundamental assumptions.

If you're saying that it's only because you don't really understand them. Mathematics was widely assumed to be complete, consistent, and decidable and then Alan Turing's Halting Problem came along and blew that out of the water. So it's been mathematically proven that not everything in mathematics is provable. Seems paradoxical to me! I guess that means the field of mathematics is just a weird superstition we should mock, right?

The sandwich analogy doesn't work, because there are not enough variables to cause significant chaos to the point of where a will can be proven. Will implies thinking and decision making in a chaotic environment so as to assume intelligence, but being only able to choose three choices and starting out with 2 demonstrates no more intelligence then random chance.

Intelligent choice is part of free will, because otherwise it is only instinctual choice. But intelligence by nature allows malevolence, because it allows you to create choices where there were none.

Also, a paradox doesn't disprove the existence of a god - if anything, any omnipotent being of any sort would be paradoxical by nature, as omnipotence can only exist in a paradoxical state. If you're wondering how that could be possible, light is a good example - it is both a wave and a particle, and yet it exists. Being a paradox doesn't exclude the possibility of something existing.

Lastly, omnipotence doesn't exclude desire. For example, if you suddenly gained omnipotent abilities, would you actively use them all? Would you change certain things? Would you change yourself? Would you create something?

Why?

The same questions could be true for any omnipotent being.

All that said, this simplified chart is missing some options, but then condensing philosophy into a simplified chart is already quite reductivist anyhow.

You can’t have free will without the option to choose anything. If you can’t choose evil you don’t have free will it’s just a semblance of free will. If you’d prefer a semblance of free will that’s valid

Can you do everything you want to, like fly by flapping your arms? No? Still you say you have free will. Can you buy a rocket and send it to mars? You cant? Still you say you have free will. Limited choices do not mean that you do not have free will.

Adding on to this, God is supposed to be able to know the future so at the moment of creation knows exactly how it'll all play out. Ignoring how this alone would mean many versions of free will wouldn't be possible, God could simply only create the people that would freely choose the right things. Why create those that He knows will just go to hell?

I choose hedbidittle!

Oh! I can't have hedbidittle, because it doesn't exist. It's not even a concept.

Well then, I guess I don't have free will.

How does free will mean absolute power?

Well I didn't choose my depression, it's origin is neuro-chemical. My free will and everyone else's would be perfectly unchanged if I didn't have said depression. Still I'm suffering every day from it and struggling greatly. How do you explain that?

Have you considered that maybe God, who is love according to the Bible, designed this universe to be a complete demonstration of love? How can you fully demonstrate love if you don't show what it means to love someone who's evil and considers you an enemy, or someone who doesn't even believe you exist, or someone who once thought they knew you but were being deceived by people with evil motives?

If God created this universe as a demonstration of love, then why the fuck is there sections of the book where he wipes out entire families with disasters because he got angry?

"I will show you love by being mean!"

Sounds like this god is a gaslighter if you ask me.

I have considered that. There is a lot of evil (or suffering) that nobody directly causes and especially not because they're evil. Why is there depression for example? Or cancer?

As for where it came from, it was all brought about with Adam and Eve's first sin, which infected all of creation with decay. You could write a creepypasta about that. Depression's a bit more complicated because it's a thing in the mind, and there's a case to be made that it's often more directly a symptom of a separation from God, knowing on some level that something's missing - but I don't think that can be said of all depression. Either way, it still ultimately stems from the first sin.

As for why it should exist for a time, it's again necessary to be able to demonstrate love in those circumstances. It's easy to love someone who's always having a good time, but it's divine to see your love and support help to pull someone out of depression, or to comfort someone who knows they don't have long to live. (This isn't just about the love God pours out, but also the love He inspires in His people.)

obviously made by someone who hasn't read the first page of the bible (like most). 1 huge point missing, god created earth not the universe, and other gods exist in the bible but are never talked about. this information is within the first couple pages of the bible. some translations can also make this harder to understand.

These verses seem to suggest he did create everything, and that "the heavens" refers to the universe outside of Earth: John 1:3, Isaiah 40:26, Colossians 1:16, Psalm 8:3-4

Christianity is fundamentally a monotheistic religion. Yes, there are other heavenly people but ultimately god creates everything

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.

Genesis 1:1, emphasis mine. I haven't read the Bible in... Fuck almost 20 years and I could still remember that one because its the first line

How can one experience pure joy without the contrast of sorrow? Stop trying to personify God. Try smoking DMT, then call yourself an "athiest".

I dare you

Wait, so experiences you have while disabling your faculties responsible for rational thinking should for some reason overrule decisions made while you're not under influence and in sound judgment? What kind of advice is that?

Cats can speak English, dude, trust me. Once I got real high and totally understood everything this cat was telling me.

You can not make such statements without at least offering one of these

I worked with a guy who told me when he was on DMT he talked to little green aliens

Which religion did DMT make you start believing in?

No specific religion, but I saw evidence of a beautifully designed, perfect "machine" all around me. I felt in tune with some sort of higher power, whatever you want to call it.

You don't need to experience bad things to enjoy good ones... They are separate unlinked things. Like you don't need to have tasted sour in order to have the ability to taste sweetness.

as a fellow psychedelics enjoyer - I'm an atheist. I can understand how psychedelics could cause you to become a believer of some religion or overall spirituality. But my man, you were on drugs. Yes they're great tools for self growth and really fun too, but everything you saw came from within your head. You've found within yourself the need for a belief that there's a diety or some sort of grand plan behind it all sure, but you did not find god.

what about we tolerate each other's beliefs as fellow humans?