Why most polls overstate support for political violence

Why most polls overstate support for political violence

Why most polls overstate support for political violence

A new poll from NPR, PBS, and Marist College published on Wednesday, Oct. 2, shows a “striking change in Americans’ views on political violence.” We have grown much more violent as a country over the last year, NPR reports, with the share of U.S. adults who agree with the statement “Americans may have to resort to violence to get the country back on track” growing from 20 to 30% over the last 18 months.

This is scary data indeed. In NPR’s coverage of the poll, Cynthia Miller-Idriss, a professor at American University, says the data is “horrific”: “It’s just a horrific moment to see that people believe, honestly believe that there’s no other alternative at this point than to resort to political violence.” Where does America go from here?

But here’s the thing: The NPR/PBS/Marist poll did not ask people if they believed “there’s no other alternative at this point than to resort to political violence.” The survey asks adults whether or not they agree with the statement that people “may have to resort to violence in order to get the country back on track.” This is comparatively a much weaker statement and comes with a potentially heavy dose of measurement error. Respondents are asked to imagine a hypothetical scenario in which they’d have to commit acts of violence against a vague, unspecified victim. Maybe that means taking up arms against the government or their neighbors, or perhaps it just means throwing a rock at a cop or through a shop door.

The problem with polls and reports like this, in other words, is that they are not asking about the “political violence” we are imagining in our heads: An insurrection at the Capitol; driving a car through a crowd of protestors; shooting an activist you don’t like with a sniper rifle. The unfortunate reality (especially for those of us who care about democracy and what the people think) is that this survey does not ask whether Americans support certain acts of violence against their neighbors, even though that’s what the poll is being used as evidence for.

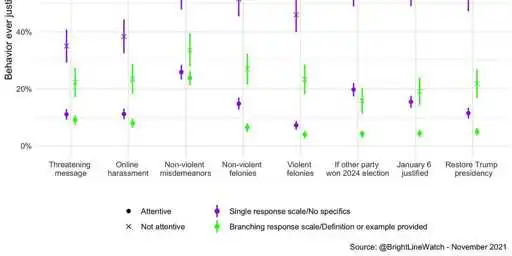

This disconnect between what is being polled and what is being talked about is part of a broader pattern I’ve pointed out in my recent coverage of political violence: Most polls overestimate mass support for political violence. I explain why this is the case, and why this is important for everyone from pollsters to elite journalists to casual news consumers to reckon with.

Fantastic article. I've had similar thoughts when reading articles on that Marist poll in particular, it seemed like a much weaker statement than most of the coverage was implying.